Utility Functions and Choices#

Introduction#

Utility functions are mathematical expressions that indicate an individual’s preferences for different choices, outcomes, or states of the word. They give a numerical value, known as utility, for each available option, outcome, or state of the world. The utility can be considered a proxy for happiness or satisfaction. Thus, a larger utility is always better than a smaller utility.

Utility functions are used in economics to model preferences and choices and predict consumer behavior. They are also used in decision theory, game theory, and other fields that study human behavior. Thus, utility functions are vital to the theory of choice, as they can be used by individuals to assign numerical values to different available options (Definition 1):

Definition 1 (Ordinal utility function)

An individual decision-maker (agent) is given a set of \(n\) objects or features, \(X=\left\{x_{1} \dotsc ,x_{n}\right\}\). A utility function ranks the agent’s preference for combinations of these objects or features:

where \(u\) is a real number called the utility which has units of utils.

The utility function \(U:X\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is unique only up to an order-preserving transformation.

Utility functions are

ordinal, i.e., they rank-order bundles but do not measure differences between bundles

Rational choice theory#

Rational choice theory is founded on the idea that individuals make decisions that maximize their utility. The theory assumes that individuals always make prudent and logical decisions that provide them with the highest personal utility. In other words, when faced with competing alternatives, a decision-making agent will always choose the option that maximizes their utility.

The utility function \(U:X\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) can be used to rank order the preference for different choices. For example, suppose we have two bundles of goods, services, or states option(s) \(A\in{X}\) and \(B\in{X}\) that we must decide between:

If the decision maker strictly prefers option \(A\) over \(B\), denoted as \(A\succ{B}\), the utility \(U(A)\) is always greater than \(U(B)\), i.e., \(U(A)>U(B)\).

If the decision maker is indifferent between option \(A\) and \(B\), denoted as \(A\sim{B}\), then the utility \(U(A)=U(B)\).

If the decision maker weakly prefers or is indifferent between option \(A\) over \(B\), denoted as \(A\succsim{B}\), then the utility \(U(A)\geq{U(B)}\).

Key Idea of Rational Choice Theory

When faced with competing alternatives, i.e., different options \(A\) and \(B\), a rational decision maker will always choose the option that maximizes their utility.

Utility functions#

To better understand utility functions, let’s explore them further. Utility functions are utilized to express preferences for various outcomes by assigning a numerical value to each option, which is referred to as utility and measured in utils. Here are some properties that a utility function should possess:

Completeness: A utility function should be able to rank all possible outcomes or alternatives. In other words, for any two outcomes, the utility function should tell us which one is preferred or whether they are equally preferred.

Transitivity: If outcome A is preferred to outcome B, and outcome B is preferred to outcome C, then outcome A must be preferred to outcome C.

Monotonicity: If more of a good is always preferred to less, then the utility function should increase in that good. Conversely, if less of a bad is always preferred to more, then the utility function should decrease in that bad.

Continuity: Small changes in the outcome or alternatives should result in small changes in the utility function.

Concavity: The utility function should be concave if the person exhibits diminishing marginal utility. This means that as a person consumes more of a good, the additional satisfaction gained from each unit consumed decreases.

These properties help ensure that a utility function accurately represents a person’s preferences and can be used to make rational choices between alternatives.

It’s important to note that utility functions, or their parameters, are subjective and may differ from one person to another. There are various types of utility functions, and we’ll examine some examples and their characteristics:

Linear utility function assumes that an individual’s utility is directly proportional to the quantity of goods or services consumed, and is represented by the equation \(U(x) = \sum{\alpha_{i}x_{i}}\), where \(\alpha_{i}>0\) is a positive constant, and \(x_{i}\) denotes the quantity of good or service \(i\) consumed.

Logarithmic utility function assumes that an individual’s utility is a function of the logarithm of the quantity consumed, and is represented by the equation \(U(x) = \ln(\alpha^{T}\cdot{x}+\beta)\), where \(\beta>0\) is a positive constant, and \(\alpha^{T}\cdot{x}\) is the scalar product of the vector of parameters \(\alpha\) and goods or services \(x\), where \(x_{i}>0\) and \(\alpha_{i}>0\).

Exponential utility function assumes that an individual’s utility is proportional to the exponential of the quantity consumed, and is represented by the equation \(U(x) = e^{\alpha^{T}\cdot{x}}\), where \(\alpha^{T}\cdot{x}\) is the scalar product of the vector of parameters \(\alpha\) and the vector of goods or services \(x\), where \(x_{i}>0\) and \(\alpha_{i}>0\).

Cobb-Douglas utility function is commonly used in economics and assumes that an individual’s utility is a function of the quantity of two or more goods consumed, and is represented by the equation \(U(x_{1},\dots,x_{n}) = \prod{x_{i}^{\alpha_{i}}}\), where \(\alpha_{i}>0\) are positive constants, and \(\sum{\alpha_{i}}=1\).

Leontief utility function assumes that an individual’s utility is based on the minimum amount of each attribute or variable required to achieve a certain level of satisfaction. The function is represented by the equation \(U(x_{1},\dots, x_{n}) = \min\left\{x_{1}/\alpha_{1},\dots,x_{n}/\alpha_{n}\right\}\), where \(\alpha_{i}\) are the minimum amounts required for each variable, and \(x_{i}\) are the quantities consumed for variable \(i\), or the system state in configuration \(i\), etc.

Linear utility functions#

A linear utility function assumes an individual’s is directly proportional to the decision or feature variables, e.g., the quantity of a good or service consumed, the state of the world, etc. A linear utility function is given by:

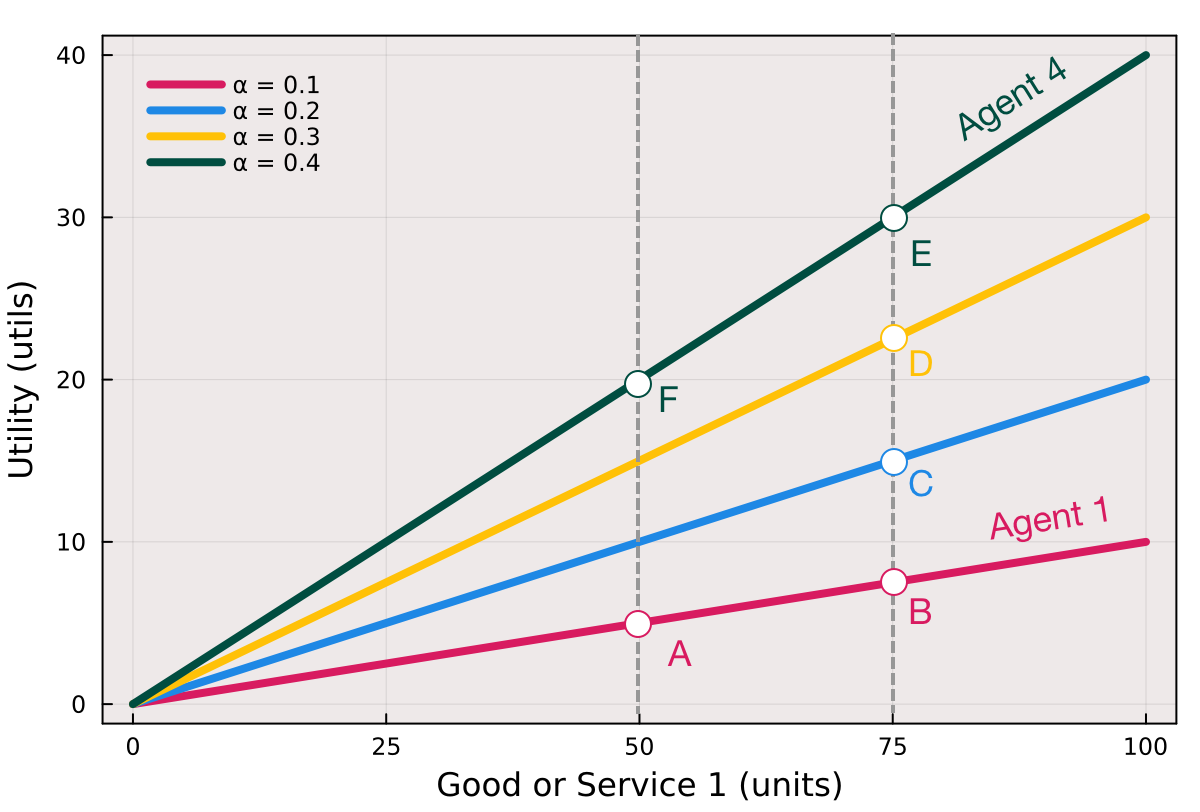

The term \(\alpha^{T}\cdot{x}\) denotes the inner (or scalar) product between the \(n\times{1}\) parameter vector \(\alpha\) and the \(n\times{1}\) vector of feature variables \(x\), where \(x_{i}\geq{0}\) and \(\alpha_{i}>0\). Let’s consider a one-dimensional linear utility function for four decision-making agents with \(\alpha_{1}<\alpha_{2}<\alpha_{3}<\alpha_{4}\) where the features are the quantity of a good or service (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Linear utility function in one dimension as a function of the quantity of good or service consumed and the values of the utility function parameter \(\alpha\).#

Each agent has a different utility value at the consumption of 75 units of \(x\), indicated as points B, C, D, and E. The agent with the highest value of \(\alpha\), Agent 4, has the highest utility value at point E, while the one with the lowest value of \(\alpha\), Agent 1, has the lowest utility value at point B.

Despite the difference in absolute utility values among the agents, their preferences remain the same. For instance, Agent 1 strictly prefers \(B\succ{A}\) , which means that they would choose to consume 75 units instead of 50 units of \(x\). Similarly, Agent 4 strictly prefers \(E\succ{F}\).

A linear utility function has constant constant marginal utility, meaning the satisfaction gained from each additional unit of \(x\) remains constant.

Implementation#

We used the VLDecisionsPackage.jl to build an instance of the VLLinearUtilityFunction utility function model. We then plotted the utility function using the plot command from the Plots.jl package:

1# load packages -

2using VLDecisionsPackage

3using Plots

4using Colors

5

6# setup colors -

7colors = Dict{Int,RGB}()

8colors[1] = parse(Colorant, "#D81B60")

9colors[2] = parse(Colorant, "#1E88E5")

10colors[3] = parse(Colorant, "#FFC107")

11colors[4] = parse(Colorant, "#004D40")

12

13# setup ranges and parameters -

14goods_array = range(0.0,stop=100.0,step=1.0) |> collect;

15parameter_value_array = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4];

16

17# goods array -

18goods_array = range(0.0,stop=100.0,step=1.0) |> collect;

19parameter_value_array = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4];

20

21counter = 1;

22for p ∈ parameter_value_array

23

24 # utility function -

25 my_utility_model = build(VLLinearUtilityFunction, (

26 α = [p],

27 ));

28

29 # evaluate the utility function -

30 utility_array = evaluate(my_utility_model, goods_array);

31

32 # plot -

33 plot!(goods_array, utility_array, label="α = $(p)", lw=4, c=colors[counter],

34 bg=:snow2, background_color_outside="white", framestyle = :box, fg_legend = :transparent);

35

36 global counter += 1;

37end

38current()

39xlabel!("Good or Service 1 (units)", fontsize=18);

40ylabel!("Utility (utils)", fontsize=18);

Logarithmic utility functions#

A logarithmic utility function assumes that an individual’s utility is a function of the logarithm of the weighted sum of the feature variables, e.g., the quantity of a good or service consumed, the state of the world, etc., plus a constant. A logarithmic utility function has the form:

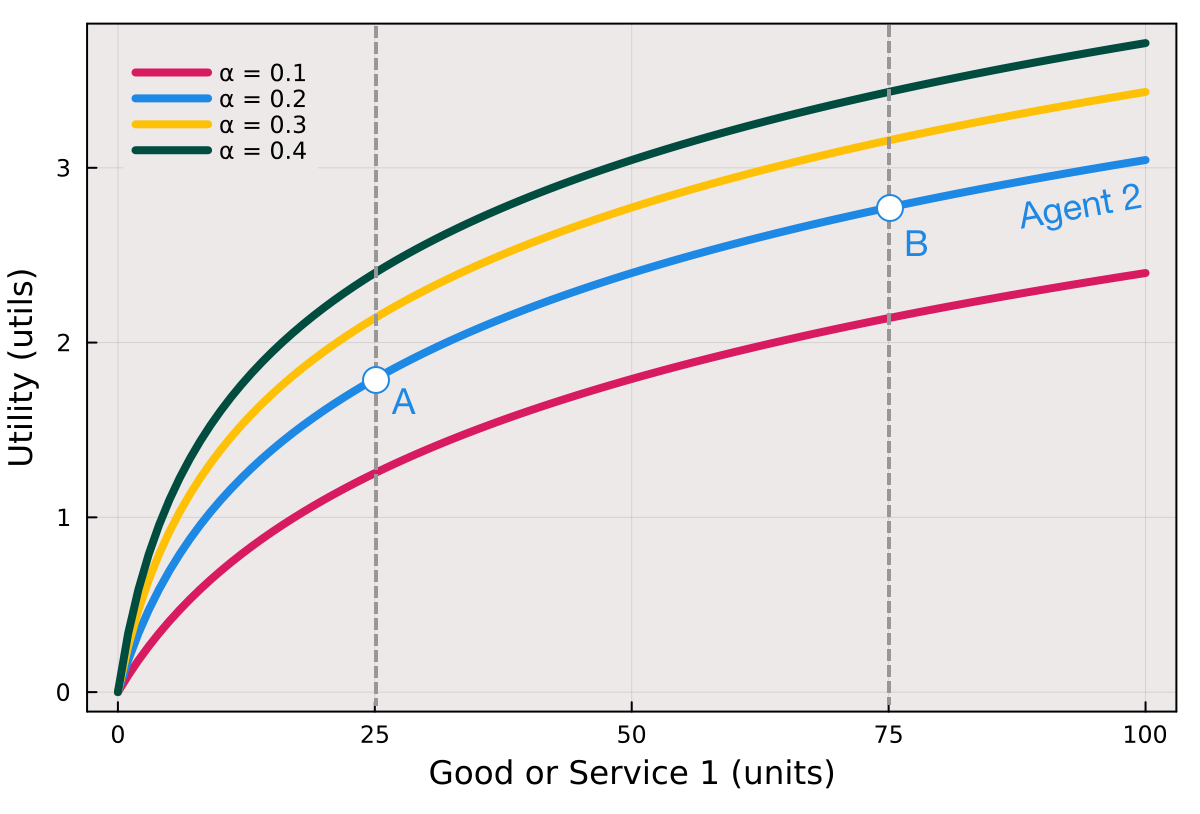

where \(\beta>0\) is a positive constant. The term \(\alpha^{T}\cdot{x}\) denotes the inner (or scalar) product between the \(n\times{1}\) parameter vector \(\alpha\) and the \(n\times{1}\) vector of featrure variables \(x\), where \(x_{i}\geq{0}\) and \(\alpha_{i}>0\). The logarithmic utility function is the log transformation of the linear utility function where \(\beta=0\). Let’s consider four agents with incresing values of \(\alpha\) but with the same value of \(\beta\) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Log utility function in one dimension as a function of the quantity of good or service consumed and the values of the utility function parameter \(\alpha\) with \(\beta = 1.0\)#

Properties of the Logarithmic utility function

Despite the difference in absolute utility values among the agents, their preferences remain the same. For instance, Agent 2 strictly prefers \(B\succ{A}\).

Unlike the linear utility function, the logarithmic utility function exhibits diminishing marginal utility, i.e., as a person consumes more of a good, the additional satisfaction gained from each unit consumed decreases.

Implementation#

We used the VLDecisionsPackage.jl to build an instance of a VLLogUtilityFunction model, and computed the utility values using the evaluate(...) function. We then plotted the utility function using the plot(...) command from the Plots.jl package:

1# load packages -

2using VLDecisionsPackage

3using Plots

4using Colors

5

6# setup colors -

7colors = Dict{Int,RGB}()

8colors[1] = parse(Colorant, "#D81B60")

9colors[2] = parse(Colorant, "#1E88E5")

10colors[3] = parse(Colorant, "#FFC107")

11colors[4] = parse(Colorant, "#004D40")

12

13# setup ranges and parameters -

14goods_array = range(0.0,stop=100.0,step=1.0) |> collect;

15parameter_value_array = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4];

16

17# main loop -

18counter = 1;

19for p ∈ parameter_value_array

20

21 # build a utility function model -

22 my_utility_model = build(VLLogUtilityFunction, (

23 α = [p], β = 1.0

24 ));

25

26 # evaluate the utility function model for the goods array -

27 utility_array = evaluate(my_utility_model, goods_array);

28

29 # plot -

30 plot!(goods_array, utility_array, label="α = $(p)", lw=4, c=colors[counter],

31 bg=:snow2, background_color_outside="white", framestyle = :box,

32 fg_legend = :transparent);

33

34 global counter += 1;

35end

36current()

37xlabel!("Good or Service 1 (units)", fontsize=18);

38ylabel!("Utility (utils)", fontsize=18);

Cobb-Douglas utility functions#

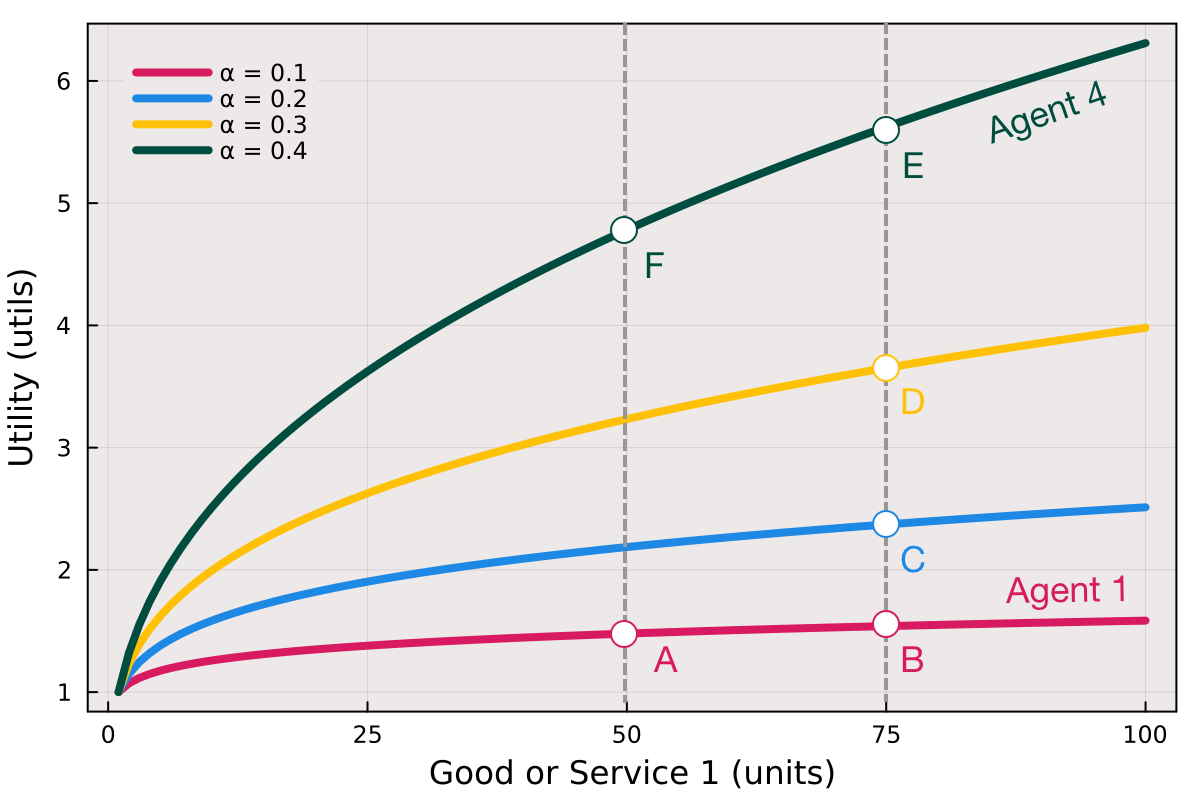

The Cobb-Douglas utility function is the product of the \(n\) feature variables, thus, it models situations where the features (consumption of goods or services, traits like make, model and color of a car, etc) occur simultaneously. Each feature variable (or good, or service) is raised to a non-negative exponent:

In our realization of the Cobb-Douglas utility, the exponents sum to unity \(\sum_{i\in{1\dots{n}}}\alpha_{i} = 1\), \(x_{i}\geq{0}\), and \(\alpha_{i}\geq{0}\).

Fig. 3 Cobb-Douglas utility function in one dimension as a function of the quantity of good or service \(x_{1}\) consumed and the values of the utility function parameters \(\alpha\). We assumed \(x_{2} = 1.0\) for all values of \(x_{1}\), and \(\sum\alpha = 1\).#

Properties of the Cobb-Douglas utility function

Different agents have varying utility values when consuming 75 units of \(x\), labeled as points B, C, D, and E. Agent 4 has the highest value of \(\alpha\) and obtains the highest utility value at point E, while Agent 1 has the lowest value of \(\alpha\) and the lowest utility value at point B.

Preferences differ among the agents. Agent 1 appears to weakly prefer \(B\succsim{A}\), which indicates that they are nearly indifferent to consuming 75 units of \(x\) versus 50 units of \(x\). However, Agent 4 strictly prefers \(E\succ{F}\).

Like the log utility, the Cobb-Douglas utility function reflects diminishing marginal utility, meaning that as a person consumes more of a good, the additional satisfaction gained from each unit consumed decreases.

Implementation#

We used the build(...) method of the VLDecisionsPackage.jl package to build an instance of a VLCobbDouglasUtilityFunction model, and then calculated the utility values using the evaluate(...) function. Finally, we ploted the utility function values using the plot(...) command from the Plots.jl package:

1# load packages -

2using VLDecisionsPackage

3using Plots

4using Colors

5

6# setup colors -

7colors = Dict{Int,RGB}()

8colors[1] = parse(Colorant, "#D81B60")

9colors[2] = parse(Colorant, "#1E88E5")

10colors[3] = parse(Colorant, "#FFC107")

11colors[4] = parse(Colorant, "#004D40")

12

13# goods array -

14number_of_steps = 100;

15goods_array = zeros(number_of_steps,2);

16for i ∈ 1:number_of_steps

17 goods_array[i,1] = i |> Float64;

18 goods_array[i,2] = 1.0;

19end

20parameter_value_array = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4];

21

22# main loop -

23counter = 1;

24for p ∈ parameter_value_array

25

26 # utility function -

27 my_utility_model = build(VLCobbDouglasUtilityFunction, (

28 α = [p, 1.0-p],

29 ));

30

31 # evaluate the utility function -

32 utility_array = evaluate(my_utility_model, goods_array);

33

34 # plot -

35 plot!(goods_array[:,1], utility_array, label="α = $(p)", lw=4, c=colors[counter],

36 bg=:snow2, background_color_outside="white", framestyle = :box,

37 fg_legend = :transparent);

38

39 global counter += 1;

40end

41current()

42xlabel!("Good or Service 1 (units)", fontsize=18);

43ylabel!("Utility (utils)", fontsize=18);

Leontief utility functions#

The Leontief utility function, first developed by Wassily Leontief who was later awared a Nobel Prize in Economics for his work, computes the utility for complementary states (or configurations) of the world, where each feature variable is scaled by a non-negative constant(s) \(\alpha\). The Leontief utility function is given by:

where \(\alpha_{i}>{0}\) and \(x_{i}\geq{0}\) for all \(i\in{1\dots{n}}\). For example, suppose we wanted to make a cheese sandwich. For this, we need two slices of bread and one slice of cheese where \(X = \left\{\text{bread},\text{cheese}\right\}\), i.e., the number of slices of bread and pieces of cheese we have. The Leontief utility function \(U(\dots)_{\text{sandwich}}\) for the sandwich is then given by:

where \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{2}\) denote the number of slices of bread and cheese we have, respectively. Let’s simulate the utility function for the sandwich using the VLDecisionsPackage.jl package.

Implementation#

We used the build(...) method of the VLDecisionsPackage.jl package to build an instance of the VLLeontiefUtilityFunction utility model, and then calculated the utility values using the evaluate(...) function:

1# load external packages -

2include("Include.jl")

3

4# initialize -

5max_number_of_bread_slices = 4;

6max_number_of_cheese_slices = 4;

7bread_array = range(0,max_number_of_bread_slices,step=1) |> collect;

8cheese_array = range(0,max_number_of_cheese_slices,step=1) |> collect;

9df = DataFrame();

10

11# # build a utility function model -

12model = build(VLLeontiefUtilityFunction, (

13 α = [2.0, 1.0], # parameters: bread, cheese

14));

15

16# main -

17for i ∈ eachindex(bread_array)

18

19 # get the number of bread slices -

20 number_of_bread_slices = bread_array[i];

21

22 for j ∈ eachindex(cheese_array)

23

24 # get the number of cheese slices -

25 number_of_cheese_slices = cheese_array[j];

26

27 # compute -

28 value = evaluate(model, [number_of_bread_slices, number_of_cheese_slices]);

29

30 # package -

31 results_tuple = (

32 bread = number_of_bread_slices,

33 cheese = number_of_cheese_slices,

34 U = value

35 );

36 push!(df, results_tuple);

37 end

38end

Using the code block above, we computed the utility function for the sandwich problem for different combinations of the number of slices of bread and cheese (Fig. Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Leontief utility function for the cheese sandwich problem. The utility function is given by \(U(x_{1},x_{2})_{\text{sandwich}} = \min\left\{\frac{x_{1}}{2},\frac{x_{2}}{1}\right\}\). The utility function is plotted as a function of the number of slices of bread and cheese.#

Marginal utility#

The marginal utility of a good or service is the added satisfaction or benefit that a consumer gains from consuming one more unit of a good or service (Definition 2):

Definition 2 (Marginal Utility)

Let \(x_{i}~(\text{for}~i\in{1\dots{n}})\) be a good or service (or a state of the world) which is a member of the set \(X\). Further, let \(U:X\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) be a utility function over the set \(X\), i.e., the function \(U\) maps a choice of goods, services or states of the world into a utility value. The marginal utility of \(x\in{X}\) is the partial derivative of \(U\) with respect to \(x\):

The marginal utility \(\bar{U}_{x_{i}}\) measures the change in the utility \(U\) resulting from small changes in \(x_{i}\).

Why is marginal utility important?#

While the marginal utility may seem like a mathematical curiosity, it has important applications. First, the marginal utility quantifies how changing the quantity of a good or service consumed (or moving from one state of the world to another) affects the utility. In particular, the change in the utility \(U(\dots)\) of the decision maker can be computed using the total differential around some starting point \(x^{\star}\in{X}\):

where \(dU\approx\left(U - U_{\star}\right)\) denotes the change in utility, \(\bar{U}_{x_{i}}\) denotes the marginal utility of \(x_{i}\) evaluated at the starting point, and \(dx_{i}\approx(x_{i}-x_{i,\star})\) is the change in \(x_{i}\).

Equation. (7) is a powerful equation that we will use to derive the marginal rate of substitution, which is how much of one thing we would willingly give up for another. Further, in the context of a trade between agents, Eqn. (7) can be used to evaluate the goodness of the trade, i.e., the change in the utility of the decision-maker experiences resulting from a trade:

If a trade is a

good tradethe change in utility should always be non-negative, i.e., \(dU\geq{0}\).If a trade is a

bad tradethe change in utility is always negative, i.e., \(dU<{0}\).

Beyond these specific applications, the concept of marginal utility holds great importance for several other reasons:

Consumer Choice and Preferences: Marginal utility helps explain how individuals make choices when allocating their limited resources (such as money and time) among different goods and services. Consumers typically aim to maximize their total utility, and they do this by allocating their resources in a way that equalizes the marginal utility per unit of money spent across different goods. In other words, consumers tend to purchase more of a good when its marginal utility is relatively high compared to its price.

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility: This law states that as a person consumes more units of a good or service, the additional satisfaction (marginal utility) derived from each successive unit tends to decrease. This principle highlights why people are willing to pay more for the first few units of a good and why demand for a product decreases as consumption increases. It also explains why variety is preferred over excessive consumption of a single item.

Pricing and Demand: Businesses use the concept of marginal utility to determine the optimal pricing strategy for their products. They understand that consumers are more likely to purchase products with higher marginal utility at a given price point. By understanding how price changes affect consumers’ perceived marginal utility, businesses can adjust their pricing strategies to maximize profits and meet demand.

Resource Allocation: Beyond individual consumption choices, the marginal utility helps societies allocate resources efficiently. It assists policymakers and governments in making decisions related to resource allocation, taxation, and public goods provision. By understanding how marginal utility varies across different individuals and goods, policymakers can work toward improving overall social welfare.

Economic Efficiency: The concept of marginal utility is closely related to economic efficiency. Efficient resource allocation occurs when the last unit of a good is distributed so that the marginal utility is equal across different goods. This ensures that resources are allocated to their most valued uses, leading to a more productive and prosperous economy.

Consumer Surplus: Marginal utility is used to calculate consumer surplus, which represents the difference between the total amount consumers are willing to pay for a good and the amount they pay. Consumer surplus is a measure of the net benefit consumers receive from their purchases, providing insights into the overall economic welfare of consumers.

In conclusion, the concept of marginal utility helps economists, businesses, and policymakers understand how individuals make choices and how markets function, ultimately contributing to a deeper understanding of financial systems.

Computing marginal utility#

The marginal utility of a good or service can be computed analytically or numerically. For example, the marginal utility of a good or service for an agent that is governed by a linear utility function is constant and independent of the amount of the good or service consumed:

If both a product, such as potato chips, and a consumer, like yourself, follow a linear utility function, then the additional satisfaction gained from consuming each unit is constant and not influenced by the quantity already consumed. Thus, the first chip is just as enjoyable as the last.

Symbolic marginal utility#

Computing the marginal utility of a linear utility function is straightforward. However, most utility functions are not linear (and can be quite complex). Thus, let’s use symbolic manipulation tools to compute the partial derivatives. For example, suppose an agent is using a concave utility function, e.g., the Cobb-Douglas utility function, then the marginal utility is given by:

where the \(j=1,i\) notation denotes the exclusion of index \(i\). As \(x_{i}\rightarrow\infty\), the marginal utility \(\bar{U}_{x_{i}}\rightarrow{0}\) if \(\alpha_{i}<1\). Thus, the satisfaction gained from comsuming an additional unit of a good or service (or moving between states in a world) decreases as the amount consumed increases.

To compute analytical expressions for the marginal utility, instead of remembering the differentiation rules from calculus, we can use one of many Computer Algebra Systems (CAS), e.g., the Symbolics.jl package in Julia or the SymPy library in Python.

Sample code to compute the marginal utility for the two-dimensional Cobb-Douglas utility function using the Symbolics.jl package:

1# load the Symbolics.jl package (assumed to be installed)

2using Symbolics

3

4# declare variables (symbols in the eqn)

5@variables x,y,α,β

6

7# Build differential operators for x

8Dₓ = Differential(x);

9

10# define the utility function

11U = (x^α)*(y^β)

12

13# compute the derivative -

14∂Uₓ = Dₓ(U) |> expand_derivatives;

15

16# print -

17println("The value of ∂U/∂x = ",∂Uₓ)

Numerical marginal utility#

However, sometimes it may not be convenient to analytically compute the derivative, e.g., the utility function is complicated or we need a numerical value, e.g., when evaluating the goodness of a trade. You can always approximate the value of the marginal utility using a finite difference approximation, or automatic differentiation approach.

Sample code for automatic differentiation of the Cobb-Douglas utility function using the ForwardDiff.jl package:

1# load the ForwardDiff package

2using ForwardDiff

3

4# Cobb-Douglas utility function

5function U(x)

6

7 # initialize

8 α₁ = 0.5;

9 α₂ = 1.0 - α₁

10

11 # return

12 return (x[1]^α₁)*(x[2]^α₂)

13end

14

15# Estimate the MU -

16x = [20.0,7.20]; # point A

17U = ForwardDiff.gradient(U,x);

Discrete Choice Models#

Discrete choice models can be used to select between competing alternatives, such as goods, services, or states of the world, based on modeled and unmodeled factors. Developed by McFadden and coworkers in the 1970s and 1980s [Baltas and Doyle, 2001, McFadden, 1973, McFadden, 1980], McFadden was later awarded the Nobel Price in Economics for his work on discrete choice models.

Discrete choice models assume that people make decisions based on factors that are known to the decision maker, but perhaps unknown to an observer. Thus, there are observable features of the decision, and there are unobservable features that influence the decision that are not modeled. For example, suppose a person chooses one car over another based on its price, fuel efficiency, safety rating, and brand. However, the decision maker also consideres style or color as important, but these features are unobserved. Utility function of this type of decision take the form:

where \(U_{ij}\) is the utility of alternative \(j\) for individual \(i\), \(V_{ij}\) is the deterministic component of the utility, i.e., the utility associated with the observable features, and \(\epsilon_{ij}\) is the random component of the utility.

Random utility functions (RUs)

Discrete choice utility functions incorporate randomness into the utility calculation to account for unmodeled factors that affect decision-making. This randomness arises not from the world but from our inability to capture all influencing factors.

Logit choice models#

The logit model assumes that the error terms \(\epsilon_{nj}\) are independently, identically distributed (i.i.d) extreme values following a Gumbel distribution. Given this assumption, and some algebraic manipulation, the probability that individual \(i\) chooses alternative \(j\) from a collection of \(J\) choices in a logit model can be shown to be:

where \(P_{ij}\) is the probability that individual \(i\) chooses alternative \(j\), \(V_{ij}\) is the deterministic component of the utility, i.e., the utility associated with the observable features, \(J\) is the set of all alternatives and \(\lambda\) is a scale parameter. The scale parameter \(\lambda\) is a positive constant that controls the degree of randomness in the model. The larger the value of \(\lambda\), the more random the model becomes.

Summary#

In this lecture, we’ll developed tools to compute rational choices and explored some mathematical and philosophical properties of utility functions:

Rational choice theory is a framework that seeks to explain human behavior by assuming that individuals make rational choices based on their preferences and goals. This theory suggests that people are motivated by self-interest and will choose actions that maximize their benefits, i.e., their utility while minimizing their costs.

Marginal utility describes the added satisfaction or benefit that a consumer gains from consuming one more unit of a good or service. This theory operates on the premise that as a consumer increases the number of units consumed, the satisfaction or benefit from each extra unit decreases. The concept of Marginal Utility is crucial in shaping consumer behavior, prices, and market equilibrium.

Discrete choice theory is a framework for modeling choices made by individuals from a set of discrete alternatives. It is used to model the behavior of agents who have to choose among a finite set of alternatives. The theory is used in many fields, including economics, marketing, transportation planning, and environmental science.